- Home

- Thomas Rydahl

The Hermit Page 2

The Hermit Read online

Page 2

He drives away from the city’s light and into darkness. The grey road ends and becomes a pale track. He presses down hard on the old Mercedes’ creaky gas pedal. Gravel plinks against the undercarriage.

The image of the hairdresser’s daughter opening the door returns to mock him. Now in socks – hair rumpled and a little glass of whisky in her hand. A fantasy only a horny man can imagine. That’s something he hates about growing old. Going from the physicality of a youth lacking spirit to pure spirit lacking physicality. To the point where the best moments are comprised of thoughts, of conceptions of the future, of reminders from way back when. For almost eighteen years he’s imagined intimacy with a woman. Imagined it. Even when he was with Annette, he imagined it. Back then it had just had a more concrete means of expression, back then it resembled intimacy with everyone else but her, right up until he was no longer near her.

His feet shift from the gas pedal to the brake. In the centre of his headlights’ bright yellow cone he sees a giant object lying in the middle of the road.

The Little Finger

1 January–3 January

4

At first he thinks it’s a fallen satellite, then he sees that it’s a car, an overturned car.

It’s a bloody Montero, a black Montero like Bill Haji’s.

It is Bill Haji’s.

It’s four or five hundred metres from the spot where they’d passed one another, but how long ago was that? An hour? He can’t make any sense of time. Maybe the Rusty Nail went to his head after all.

He cuts his engine but leaves the headlights on, so he can see the car. He hears the ocean and the soft hum of the Montero’s motor. The dust settles.

He’s about to turn on his CB radio and contact dispatch; it’s the best he can do. Then he hears some rapping sounds, as if someone’s trying to communicate or get free. He gets out of his car. He calls Bill’s name. He calls as though they know each other. Bill Haji. They hardly know each other. Everyone knows Bill Haji. A colourful, obnoxious person. Never at rest, always on his way to or fro. Erhard has driven him a few times. The first time was to the hospital. And after that – upon request: a couple of trips to the airport and home to Haji’s villa some miles away. Haji arrived from Madrid with four or five suitcases and a young man who seemed tired. They were the same suitcases both times, but not the same guy. Erhard didn’t care about the rumours, or how Haji lived his life. One shouldn’t get involved in that kind of thing. As long as the boys are over eighteen and have made their own choices.

– Bill Haji, he repeats.

The car is smashed up. It must have rolled a good distance. Stupid Montero. No better than Japanese cardboard. There’s a long trail of glass. Which suggests to him that the vehicle skidded along the road. He calls again as he walks around the car and peers through what might have been the windscreen, but is probably a side window. There’s no one inside. Neither Bill nor any of his boys. Erhard breathes easier. Even though he doesn’t much care for Bill Haji, he feared seeing him mashed between the steering wheel and the seat like a blood-gorged tick. The vehicle is empty; one of the doors is open, hanging from its hinge. Maybe he’s gone after help or was picked up by his sister, who’s always close by Bill Haji, whenever he sees him downtown or at La Marquesina. He bends forward and touches the car. It’s still warm.

For a moment the darkness and the car fade away, and the entire sky is lit up in shades of green and cyan and magenta, and it’s as if hundreds of eyes are looking back at him.

5

The sky above explodes. Erhard stares across the vehicle. More booms follow in choppy rhythm, streaks and flashes of light. At first he thinks that they’re emergency lights from a ship. Then he remembers that it’s New Year’s Eve and he spots the stream of fireworks down in the city. When his eyes adjust to the darkness again, he sees something moving right in front of him.

Sitting on top of what was once the car’s exhaust is a dog.

Two dogs.

They’re watching him like cute puppies heading out for a walk. They’re wild dogs. No one knows where they come from. Maybe from Corralejo seven miles away. Whether they are sitting there or running along the edges of cliffs in the moonlight, they’re handsome animals. In the daylight they appear emaciated and beaten, like old blankets. They’re a plague to anyone who raises sheep and goats, and among bored young men they’ve become something one shoots as target practice from the bed of a lorry. And yet somehow there are more of them than ever. Erhard guesses that ten or fifteen of them are out there in the darkness. Maybe Bill Haji hit one of them, maybe that’s why he crashed. One of the dogs is drooling. Erhard stares through its forelegs.

Even though most of his face is gone, he can still recognize Bill Haji’s remains. There’s nothing left to save. Maybe he was dead before the dogs got to him. His famous sideburns look like rabbit fur turned inside out.

Then he sees it.

6

It’s lying right behind the left front wheel, in darkness. He only sees it because it sparkles a little each time the fireworks explode in the sky. At first he’s not sure what it is. There’s heat in the reflection, an amber radiance. He guesses that it’s some copper or something embossed in gold, perhaps part of a pair of sunglasses or a cord sliced in half. For a moment he wonders if it’s a gold filling, then he sees the fingernail and the small folds around the joint. He notices that the broad ring is surrounded by flesh.

It’s Bill Haji’s engagement ring. On Bill Haji’s ring finger. Ten minus one.

He doesn’t want to go around the vehicle, so he reaches for it; he doesn’t even know if he can reach it. It’s only a metre or two away from him on the other side of the car. He stretches across the undercarriage, but the two dogs glance up from their dinner. One bares its teeth and repositions its front paws, ready to spring. Erhard might be able to snatch the finger, but not without having a dog stuck to his arm.

He walks slowly back to his own car and snaps on the high beams. He blinks the lights on and off a few times until the dogs glower at him in irritation. Then he lays his hand against the centre of the wheel and puts all his weight into it. The car emits a few shrill honks that most wouldn’t believe belonged to a Mercedes. He presses the horn until the two dogs on the other car hop sluggishly down like junkies and slink off a few metres into the darkness.

He hurries to the Montero by the glow of his high beams. As fast as he can. It has been several months, maybe years, since he last ran. Although it’s only a few metres, it feels like forever. As if the dogs have already seen him and are moving towards the vehicle again. As if his legs are unreliable and can’t carry him all the way there and back again in a single evening. He doesn’t get as close to the car as he wishes but leans across the overturned Montero to reach for the ring. A mere half-metre away.

He’s splayed out just opposite what remains of Bill Haji’s head and face, gazing through a red-blue clot at open but extinguished eyes.

Find the boy.

The sentence emerges so loud and clear through the noise of the fireworks that, for a moment, Erhard thinks it’s coming from the radio that’s still playing. Or maybe one of the dogs, as far as he fucking knows, is suddenly talking. He stares into Bill Haji’s eyes and it’s almost as if the voice is coming from them, from the dark circles slowly glossing over in death. He’s heard the voice before. It’s a voice he recognizes. Maybe it’s Bill Haji’s. Maybe it’s just something he said out loud, for God knows what reason. He can’t even remember what he said, only that the words were pleading.

Then he sees the finger again and hoists himself forward. The undercarriage is still warm. Not hot, but warm like a rock. The fireworks die out, the final salute blasting above the coast, a green network that sprays silver. Silence follows. Not quite silence. The engine groans. And the dogs’ plaintive yips have become a supersonic whine, which must be the sound they make right before

they turn vicious. Something rustles just below the car. Erhard crawls forward on his belly, stretches his arm, and clutches the finger. It’s cold. Bristly. And incredible.

Nine + one, he thinks.

7

Erhard runs back to his car and hurls himself into the front seat, then slams the door. Since he discovered the overturned car, he’s felt perfectly sober, almost hung-over, and now his drunkenness returns with a snap. Not only the dizzying sensation, but also a bizarre elation, a joy.

It’s as if his eyes, body, and mind are doing short-circuited mathematics. With his own nine fingers and Bill Haji’s one that makes ten fingers. It stirs a pleasure all the way down in his belly, hell, down in his cock – as if having a new finger in his possession has strengthened his libido. He knows that it’s wrong, knows he’s imaging it, but even though it’s not his finger, the sum total of fingers makes him whole in a way he’s not felt in a long time. In the same way that losing his finger eighteen years before represented a repulsion, a conscious subtraction, this finger returns his balance to him.

He tosses his socks and plops in bed with a buzzing head. The generator has run dry, because he forgot to turn it off when he left. Tomorrow, tomorrow he’ll have a look at it. Although the night is quiet, when the wind shifts direction it sounds like dogs snarling.

If they eat him there will be nothing to bury. If there’s nothing to bury, he’s not dead. Bill Haji’s sister is one hard woman who looks like a man. She’ll have to say her goodbyes to an empty coffin.

The finger on a hand, Bill Haji’s hand, which once hailed Erhard on the high street. His boyfriend was sick. Bill Haji caressed him all the way to the hospital. What Erhard recalls most of all was the scent of watermelon and the stack of 500-euro notes Bill Haji wanted to pay with. To make change, Erhard had to run inside a kiosk. The finger. Bill Haji’s hand. Bill Haji’s sideburns. The most Irish thing about the man.

He fumbles in the dark of his bedroom to find the telephone. There’s been an accident. Hurry, he says. It’s like leaving a message. He gives the address, trying to alter his voice so that he sounds more Spanish. Los perros se lo han comido. The dogs have eaten him. The man on the other end of the line doesn’t quite understand.

– Your name? May I ask who is calling?

A long silence. Erhard wants to hang up, but he can’t find the off button in the dark. He runs his hand up the twisted cord until he locates it.

– Hello, the man says.

Erhard hangs up. Once again, the house is shockingly quiet. All that remains is the wind swooshing across the rocks. The new year has already come to the islands. The finger is tucked underneath his pillow like a lucky coin.

8

On Tuesday, he rises early and goes for a drive before reporting to dispatch and picking up his first fares. His first trip is always down to Alapaqa, the fisherman’s village, where the seagulls scream and you can get the best coffee on the island. Aristide and his wife Miza brew it themselves, grinding it with Miza’s father’s old Arabic grinder, which covers the length of a desk. The sweet coffee is practically purple. The island’s best. Even though he can’t say that he’s tried every place that offers coffee, he’s probably tried most of them.

– You look chipper today, Erhard, Miza says. Erhard gives her cousin a terse hello. She’s staying with Miza temporarily and enters the cafe in her bare feet. She’s a motorcycle-girl with a filthy mouth. He doesn’t care for that, but he likes her hair. When she’s standing with her back to him, he can see it. Dark and long, all the way to her thighs. As Erhard drinks his coffee, the cousin talks about a bodybuilder called Stefano. Not a nice guy, Erhard would say if she asked, but she doesn’t. She doesn’t ask anything. Instead she prattles on about the bodybuilder’s chicken brain and a TV he smashed and all the money he spent on some skanky bitches at a bar in Puerto. Miza cleans the cafe while listening, giving Erhard a glance. Maybe women aren’t always worth it, her glance says.

Maybe men aren’t, either.

There’s also a shower at Miza’s that he uses. It’s in a small shed where the fishermen clean and dry large fish. Through the years it has become a kind of public shower for surfers, fishermen, and one particular taxi driver who doesn’t have his own. On a good day there won’t be any fish hanging in the room. Today a huge swordfish dangles from a hook jammed in its mouth.

9

He hauls in a meagre 120 euros. He falls into a good rhythm, with customers turning up just as quickly as he drops them off. He keeps the finger in his pocket, not daring to remove it. He’s tried to slide the ring off, but it’s stuck, wedged all the way to the bone. Bill Haji wasn’t fat, but his finger is either swollen or so fleshy that the ring’s now tight. He imagines a young Bill putting it on. When the finger has dried a bit, maybe he’ll be able to pry the ring free. As long as the finger doesn’t snap in two or crumble like dry clay.

After siesta he heads down to Villaverde. He parks on a quiet road behind the Aritzas’ white mansion. Each year, always a few days after New Year, the Aritzas host visitors from the mainland, and their little niece Ainhoa plays Gershwin’s ‘Concerto in F’.

He arrives half an hour early and tunes the piano while the women drink champagne on the terrace and the men stare into the Steinway, offering commentary. Not to Erhard, but to each other. André Aritza is a friendly man in his late forties with unusually thick glasses. Ever since Erhard blurted out that he knows nothing about computers, nor has any interest in them, André Aritza has been cool to him. The man obviously earned his fortune on computers and ships and navigation. One of the nouveau riche – of which there are more and more. Odd, spineless men with young trophy wives who maintain the household for them and their children.

Today, three of those squinty-eyed inventor types are pointing into the housing at the hammers going up and down, and they refer to Erhard standing right beside them as the Piano Tuner. The brother-in-law says something about a mobile phone, how it can tune the piano. Very, very smart, the brother-in-law says. Tell me, how much do you pay the Piano Tuner? André Aritza replies: Way too much for way too little. Then get that app, the brother-in-law says, it only costs 79 cents. The men laugh. The sad sack will be unemployed soon, says the youngest of the inventor types. Erhard’s busy with the tuning fork, his head all the way inside the housing. He hears a lot of that kind of thing. Also when he drives his cab.

He feels the finger in his pocket. Actually he can’t feel it, just knows it’s there. It gives him strange ideas. Like the desire to rip the strings out of this goddamn piano. Like the desire to play études with André Aritza’s head mashed onto the keys. But it also makes him want to let it go. To be calm and not waste his opportunities.

Reina Aritza tries to gather the company in the dining room. There’s a suite behind some closed sliding doors. The entire house smells of overcooked lobster. Erhard takes his time finishing as the party breaks up and begins drinking champagne in front of the windows, where there’s a view of the bay and the water. He walks downstairs to the kitchen, washes his blackened fingers, and then heads to the entranceway. Just as he’s about to close the front door, he remembers the envelope containing money that’s sitting on the small worktop. That’s always where he finds it. One hundred euros. He doesn’t need the money. If he doesn’t take the envelope he can show André Aritza that he’s not doing it for the money. That he won’t be subjected to commentary for chump-change. But it would just look like he forgot the money. He didn’t speak up when they commented negatively about him, and they’d just think the poor, confused piano tuner has forgotten his money. Maybe they would laugh at him even more.

Hell no. He goes back upstairs and past the dining room, where he hears Reina directing the guests around the table, placing men and women. She calls for André, but there’s no response. Erhard scoops the envelope off the counter and quickly peeks into the living room through the slit in the door, and he sees the ni

ece leaning against the piano gazing out the window. André Aritza is standing a little too close to her, his mouth a little too close to her ear. He’s watching her as if he expects a reaction, but one of his hands is inching up her thigh and up towards the long, silvery blouse that hangs below her waist. She doesn’t seem to be enjoying herself, but she doesn’t seem ashamed or surprised either. The only mitigating circumstance here is that she’s not his real niece, just a good friend’s daughter whom they regard as a niece. And she’s not a child, she’s a young woman, close to seventeen or eighteen years old. For someone like Erhard, who doesn’t know anything about sex or seducing women, his advances seem neither sexy nor seductive.

Behind him Erhard hears Reina Aritza on her way down the hallway.

– Señor Jørgensen, she says, when she sees him standing there with the envelope in his hand. Thank you for your help. Happy New Year to you.

Erhard turns swiftly and pushes the living-room door open. André Aritza abruptly removes his hand from his niece and stands stiff as a butler beside her, glancing at Erhard, irritated. The niece still seems indifferent. As if he’s filled her with champagne or said something to her that that preoccupies her mind. – Your beautiful wife is looking for you, Erhard says loudly.

– I see, thank you, the man says, looking away.

– The lobster is getting cold, Reina Aritza says into the living room. – Remember the champagne flutes.

– Happy New Year to you and your niece, Erhard says to André Aritza, turning his back to them and heading down the stairs. He sees a lot of this kind of thing, but still he wonders if this will be his last visit to this house. André Aritza may become even more difficult now. On the other hand it’ll be a long time before he needs to tune the piano again. He takes care of the few assignments he has. There’s no reason to make a decision now. It’ll be another year before he sees these people again.

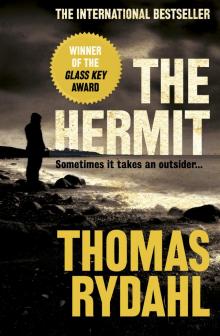

The Hermit

The Hermit