- Home

- Thomas Rydahl

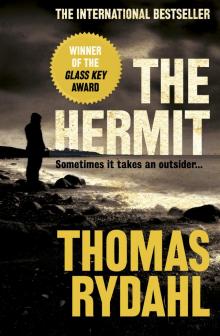

The Hermit

The Hermit Read online

THE HERMIT

Nobody knows why Erhard has left his wife and child in Denmark. All they do know is that he lives in a remote house on the island of Fuerteventura and has nine fingers. Known locally as The Hermit, he spends his days driving a taxi and tuning pianos for the wealthy tourists and islanders, and for almost two decades he has felt alone and incomplete, searching for intimacy – and that tenth finger.

Then one day a baby is found dead in an abandoned car. Called in by the police to assist in the investigation, Erhard is drawn into the mystery, suddenly desperate to solve a crime he believes might give meaning to his life. But why have the police asked Erhard for help? Why should he succeed when they have failed? And will his journey help him find something more than just the child’s killer?

A literary noir with existential undertones, The Hermit brilliantly unpicks a savage act and in doing so, offers one man the possibility of redemption, in this acutely observed, disquieting psychological thriller that has taken the international publishing world by storm.

Contents

Luisa

The Little Finger

The Whore

The Corpse

The Flat

The Cargo Ship

The Liar

Lucifia

Lily

Luisa

31 December

1

On New Year’s Eve, under the influence of a triple Lumumba, Erhard decides to find a new girlfriend. New is probably not the right word. She doesn’t need to be new or attractive or sweet or fun. Just a warm body. Just one of those kinds of women who potters about the house. Maybe she’ll hum a song or curse at him because he’s spilled cocoa on the floor. What can he ask of her? Not much. And what does he have to offer her? Not much. But it won’t get any easier. In a few years she’ll also need to empty his piss pot and shave him and pull off his shoes after an entire day in the car – if he can still drive, that is. In a few years.

The mountainside near the house is invisible; the darkness is complete. If he sits still long enough, he’ll suddenly be able to see the stars. And if he sits even longer than that, he’ll see a narrow band of shooting stars growing brighter and brighter. The silence grows, if one can put it that way. Grows like the sound of nothingness drowning out the heat of the day still whining in the rocks, and the wind’s relentless C major, and the beat of the waves lashing against the coast, and the blood that’s seeping through his body. A silence that makes him want to weep into the New Year. A silence that’s so convincing, so satiating, that it blends with the night and his wide-open eyes which feel closed. This is what he loves about living out here. Out here where no one ever comes.

Just him. And Laurel and Hardy. And here come the stars. They’ve always been there, but now he can see them. First all the specks, then all the constellations and Orion’s Belt and the galaxy like an old-fashioned punch card with messages from the Big Bang.

It’s been seventeen years and nine months since the last time. He smells Beatriz’s perfume, which practically clings to his shirt right where she’d touched him this afternoon as they parted. She suggested that he come along tonight. A half-hearted attempt, if even that. I’ve got plans, he’d said tartly, the way only an old man can. C’mon, she’d tried again, sweetly. No thanks, those people are too fancy for me. Which they were. She didn’t say anything to that. Instead Raúl said: You are one of the finest people I know. But nothing more was said about it, and when they began arranging the champagne flutes, he gave Beatriz a Happy New Year’s kiss and left. Raúl walked him out. Buen viaje, Erhard said, when they stood among the distinctive throng on the street. From the opposite pavement, the suitcase salesman, Silón, shouted Happy New Year! to them, though mostly to Raúl, whom everyone knows. Erhard headed to his car, feeling the same pang that struck him every New Year’s Eve. Another year gone like all the rest, another year looming.

Cheers, my friend. It’s good with cognac. It burns all the way down. The night is warm. His body is tingling hot now. Maybe because he’s thinking of Beatriz, her dark place, right where her breasts part and vanish into her blouse, the very source of her aroma. Damn. He tries not to think about her. She’s not the one he should be spending his time on.

The hairdresser’s daughter. He can think about her. There’s something about her.

He’s never met her. He has seen her once, at a distance. He’s often seen her image on the wall in the salon. He thinks about her. He thinks about simple events. Little scenes where she walks into the salon, the bell above the door chiming. He imagines her sitting across from him at the dinner table when he eats. Or standing in the kitchen, his kitchen, preparing steaming, sizzling food on the stove. In truth she’s much too young, absorbed in things he doesn’t understand. She’s not exactly his type. What could he possibly say to impress a young woman? She probably doesn’t even cook. She’d probably rather talk to her friends on the telephone, like all young people do. Maybe she eats noodles out of a small box while staring at her computer screen. In the image at the salon she’s a teenager and the very picture of innocence, with thick curls and big, masculine glasses. Not beautiful, but unforgettable. She’s got to be at least thirty now and apparently both sweet and quick-witted, according to her mother, whom he obviously doesn’t trust. That time he’d spotted her down the street, he recognized her light, curly hair. She crossed the street with her back ramrod straight, a purse slung over her shoulder like a real woman, and she spurted forward running when a car raced towards her. She wasn’t elegant, she was even a little clumsy. He doesn’t know why he thinks about her so much. Maybe it’s just the island eating its way into him. The whistling of the wind around the rocks and corners. Like a note of loneliness continuously rising from a piano.

It’s Petra’s fault. Her unnaturally high-pitched voice that pacifies her clients in the chair and rules out talk and counterarguments and reasonable thoughts as one thumbs through a magazine or reads an article about the island’s football team. She has this firmness about her. For her, love is something to be squeezed out of others. She talks non-stop about the daughter, clawing at Erhard’s scalp with her long nails as she tells him that she’s moved to an apartment, that she’s bought a little scooter, that she’s got a new client, that she’s broken things off with her boyfriend, that she – not the daughter – would like grandchildren, and so on. And then a few months ago she suddenly said: If only my daughter found someone like you. That’s what she said as she stood gazing at him in the mirror. And afterward: She’s not like most girls, but neither are you. They’d chuckled at that. Petra mostly.

Erhard had been completely alarmed at the suggestion. She couldn’t just say something like that. Wave her daughter under his nose. Did that mean she wanted him to ask her daughter out? Didn’t Petra know what they called him about town? Hadn’t Petra noticed that he was missing a finger? And what about the age difference? Didn’t Petra consider that? They are separated by at least thirty years; he’s the same age as her mother, older even. But the symmetry appeals to him. Generations reaching back and pulling the next generation forward, Escher’s drawings of the artist’s hand sketching itself. Five fingers on one hand and five fingers on the other. Five + five.

If only my daughter found someone like you, she’d said. Someone like him.

Not him, but someone like him.

What was that all about? Was she saying there were many like him out there? Carbon copies of men who’ve done the same things over and over for nearly a generation, without deviation, without asking questions, someone like him, gas from the asshole of the earth, here today and gone tomorrow with only the memory of the stench remaining.

Down in the city it sounds li

ke fireworks booming.

Maybe he should just do it now? Drive over there and invite her out? Right now? Then it’d be over with. He knows it’s the Lumumba talking. He knows that his courage won’t last more than two hours. Then reality will come crawling back. It’s quarter past ten. Perhaps she’s having dinner somewhere with all sorts of young men who know all sorts of things about computers. But what if she’s sitting at home just like him – watching the terrible show they broadcast on TV every year. Her mother has told him multiple times where her flat is. It’s in one of the new buildings on Calle Palangre. Right above the children’s-wear shop. It couldn’t hurt just to see whether she’s home. Maybe he can see if there’s a light on in the flat, or if there’s a light from the television glowing in the darkness.

He braces himself against the wall of his house and finds a pair of stiff trousers on the clothesline, then jams his feet through the holes. The goats run off somewhere in the darkness.

2

He drives along Alejandro’s Trail into the city.

He shouldn’t drive on that track; it ruins the car. He’s already had the axles repaired twice, and each time the mechanic, Anphil, warned him. You don’t drive down the north road, do you? Or Alejandro’s Trail? The car can’t handle it. You’ll have to get a Montero or one of the new Merceros; they can handle it, not this car. But Erhard doesn’t want a Montero, and he doesn’t have the money for a new Mercedes. Even if he had the money, he would keep his Mercedes from Morocco with its yellow seats and choppy acceleration. All the same, he takes Alejandro’s Trail. Drives past Olivia’s old house where the surfers have moved in with their boards lying on the roof, and in the darkness he can see their flags: a pair of pink knickers hanging from the end of a long stick that’s jutting from the cabin. Two guys and their friends live there. Sometimes when he passes by, in the morning, they’re sitting outside, smoking tobacco from large pipes; they wave at him, laughing hysterically. Whenever he stops the car, they’re high as poisoned goats and unable to rise from their inflatable chairs. But there’s no one home now, and the lights are out. They’re probably on the beach or downtown.

He approaches the bend that hugs the coast, a fantastic bend – especially with Lumumba up to his Adam’s apple and cheap cognac in every finger joint. It’s a pebbly, potholey road, and the entire car vibrates. Swerving when he reaches 70 mph, he feels a tickling sensation that makes him grin. He breaks wind, too, which isn’t as funny; he just can’t help himself. He’s had the problem the last few years. If he squeezes his stomach muscles even a little, a pocket of air lurches through his gut and into his underwear; it’s both painful and liberating. From there the trail runs downhill, and he hits the final curve. Through the headlights he sees a goat standing in the centre of the road, and he veers around it before glancing in the rearview mirror; it looks like Hardy, but it can’t be him, not here, not this far from the house. The goat has already disappeared in the darkness.

He’s so preoccupied that he doesn’t see the car driving towards him until it passes on the much-too-narrow road. Mostly it’s just sound, a dry whooom. A metallic shadow along the car. The side mirror gets knocked flat against the glass.

– Goddamn amateurs! he shouts, to his surprise, in Danish. He apparently hasn’t forgotten how to curse. He continues around the curve, the other car is out of sight, the red tail-lights vanished in the night. There’s no point even stopping to inspect the damage. He rolls his window down and fixes his mirror. The glass has splintered into tributaries pointing downward in eight fine lines.

A black Montero. No doubt it was the gadabout Bill Haji, who lives up the road at a ranchlike villa with horses; he’s known for taking Alejandro’s Trail fast and furious, as if the sea was ablaze behind him. Erhard’s heart should be sitting in his throat right now, but instead it’s right where it’s supposed to be, numbed by the Lumumba and agitated by the prospect of meeting the hairdresser’s daughter.

He drives off the trail and into Corralejo. The heat rises from the asphalt. Young people in small cars honk and sing. He heads down the Avenida towards the harbour, then parks in Calle Palangre. He dumps the car when he finds a vacant spot.

He plans to walk to the hairdresser’s daughter’s place. He wants to knock on her door. He’s already red-faced and embarrassed by the look she will give him when he’s standing at her door. Good evening, he will say, and Happy New Year. He’s seen her before. I’ve seen you in the photograph at your mother’s salon. What if she’s wearing one of those summer dresses with the lazy straps that are always falling to the side? Who gives a shit if she wears glasses? He’s not picky.

But when he reaches the clothing shop and glances up at the flats above, he sees that the lights are off. On every storey of the building. She’s probably watching TV. Drinking white wine and hoping someone will stop by. He needs to fortify himself with a drink. Something really strong. Just something to get his voice box going. It’ll do him no good just standing there staring like some idiotic extranjero. He walks up the street and down Via Ropia. Towards Centro Atlantico. It’s always buzzing there, mostly with tourists, people he doesn’t know. He walks into Flicks and goes directly to the bar. He orders a Rusty Nail, and even buys a round for the two gentlemen in the corner. They’re olive farmers out prowling for women and unaccustomed to city life, huddled close like mice behind a palm tree. They are practically invisible.

3

Eighteen minutes to go. On the back wall of the bar the TV’s showing images from Times Square, fireworks over Sydney Harbour, Big Ben’s long hands approaching XII. The bartender shouts Are you ready for the new year? It sounds so promising, so simple. As if one leaves behind all the old, bringing only the new into the new year. But new means nothing to him. He’s not new. He doesn’t need new. He doesn’t want new. He just wants the old to behave properly. Seventeen minutes. He can still ring the doorbell and wish her a Happy New Year. Maybe she’s wearing a negligee or whatever it’s called. She’s been sitting there drinking white wine and watching reruns of 7 Vidas, which everyone loves. Her hair is wet, she’s taken a cool bath.

A crowd of people moves to exit onto the street. He’s nearly pushed off his stool. He pays with a bill and remembers why he doesn’t frequent tourist traps: it costs more than twenty euros for whisky and Drambuie. He follows the throng out and starts back towards Calle Palangre. He crosses the street and enters her building. It was built during the Franco years, and the stairwell is simple and cobalt-blue. On the first floor he reads the names on each of the three doors. Loud music is blaring inside, but there’s no Louisa or L.

He walks up another flight. A couple stands kissing beneath the artificial light of the stairwell, but when he passes them they stop, shamefaced, and head down the stairs.

As he stands catching his breath a moment, he looks at the nameplates, then continues to the top floor. Three floors with doors equals nine doors.

On the third floor live one Federico Javier Panôs and one Sobrino. And in the centre, Luisa Muelas. The sign on her door is large and inlaid with gold, her name etched in thick, cursive letters. No doubt a gift from Petra and her husband. It’s one of those traditional items parents give their children whenever they, as thirty-year-olds, move out of their childhood home.

It seems quiet behind each of the doors. He puts his ear against Luisa Muelas’s and almost wishes her not to be home. But there’s a faint noise inside – clatters, creaks, mumbles – but perhaps it’s just the TV.

He straightens up and raps his good hand, the right, against the flat chunk of wood above the peephole. It’s four minutes to midnight. Maybe his knocks will fade into the raucous noise of New Year’s Eve.

Suddenly he sees a face in the nameplate.

The face is indistinct. A pleading, confused face dominated by two eyes wedged between a stack of wrinkles and shabby skin, topped off with a tired beard. A desperate face. In it he can see love and sorrow, he can see decades of b

ewilderment and alcohol, and he can see the cynical observer, appraising and judgemental. It’s an appallingly wretched face, difficult to penetrate, difficult to stomach, difficult to love. But worst of all it’s his face. As seen only from the rearview mirror of his car, or in the distorted mirrors above the chipped sinks of public toilets, or in shop windows, but preferably not at all. There’s only one thing to ask that face.

What have you got to offer?

In reality there’s nothing more frightening than this. The encounter. The moment in a life when one takes a risk. When one says, I want you. The moment when chance ceases, when one makes a stand and asks another to accept. The moment when two soap bubbles burst the reflection, merging into one. It doesn’t happen during a kiss, or during sex, and not even when one person loves another. It’s in the terrifying second when one dares to make a mad claim that one has something to offer another by one’s very presence.

He hears sounds behind the door now. Like stockinged feet.

– I’m coming, a soft voice says.

It’s two minutes to twelve.

He can’t do it, he just can’t. He leans over the stairwell and starts down. Down, down. He hears the door opening on the top floor. Hello? the voice says. Past the doors with loud music and outside. Onto the street. He hobbles along the wall like a rat, then cuts across the street to his car. Calle Palangre is filled with people now. There’s a group of cigar-smoking men standing beside his car, and girls astride scooters, champagne flutes in their hands.

Voices call out from the flats above. He fumbles his way into his car and wriggles it free of its parking spot. Following the one-way street, he parts the throng. A group wants to catch a ride, not seeing that his sign is turned off, but he’s not interested. He pays no mind to their hands on his windscreen or their pleading eyes. Happy New Year, asshole!, a young girl wearing a silver-covered bowler shouts at him.

The Hermit

The Hermit