- Home

- Thomas Rydahl

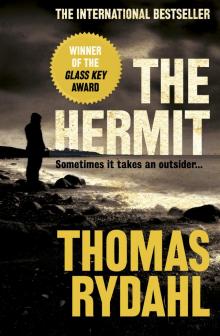

The Hermit Page 4

The Hermit Read online

Page 4

When he goes to the supermarket, he notices the coin-operated telephone in the corner, or, if he passes an electronics store – Corralejo has plenty of these – he spots, at a distance, an answering machine inside a faded box. Ever since Annette called to curse him out he’s been this way at the start of a new year. He was unable to respond to her; she just called to vent. This was in 1997, immediately after he began sending money home. She couldn’t take it. Couldn’t stomach his goddamn money. She wanted nothing from him. Nothing. You’re dead, you’re already dead. Then she hung up. The following year she called back. This time she didn’t say anything, just cried for twenty seconds. She hasn’t called since. But this year marks the eighteenth year since he left her. He’s expecting a call. Practically wishes for it. Even if she’s just crying into the telephone. But there’s nothing. Maybe she’s forgotten his number, or him. Maybe she’s remarried. There’s nothing.

He picks up every customer that comes his way, he works all afternoon and into the evening, and he works until he’s so tired that his eyelids stick together. Afterward he heads to the harbour, indiscriminately buys a bottle of wine, and sits on the pier, alone, watching young people leap into the water until the last rays of sunlight vanish from the rocky island of Isla de Lobos and the sea turns black. He staggers to the intercom at Calle el Muelle to pay Raúl and Beatriz a visit.

– Come on up, old man, Raúl says, always ready.

They open the door. She’s wearing a sheer yellow summer dress that shows off her long, tanned legs, and he’s wearing a shirt unbuttoned at the top. They welcome him like he’s their father: pleasant and receptive and happy. They’ve just mixed some mojitos. The three of them head up to the rooftop terrace.

Beatriz sits on Raúl’s lap, and they kiss. Erhard tells them about the kite surfers and Bill Haji and Mónica, the Boy-Man’s mother. Raúl says that Erhard’s the most unbelievable man he knows, and Beatriz – after mixing more drinks for them and pouring wine for herself – passes next to him, wafting her sublime perfume as she runs her hand and its long fingernails through Erhard’s thin hair.

He pretends, as always, that he doesn’t care for this, but on some nights it’s just such a hand that he fantasizes about. The nails like sharpened pencils drawing long strokes through his hair. It would be a different matter, obviously, if they really were his children, if Raúl was his son and Beatriz his daughter-in-law. But he knows they are not, and his dick knows they are not, and that’s all there is to it. He doesn’t even feel badly for Raúl. Raúl is Raúl, a real cock of the walk if ever there was one. Raúl may be his father’s son and Beatriz’s boyfriend, but no one can be sure of anything. He wants it all, but he doesn’t want to be tied down. He has it all, but he doesn’t want to own anything. Defiant and charming and always on his way into or out of a drunken stupor. In some strange way he was Erhard’s most attentive pupil. Erhard’s only pupil. At the beginning he was a foolish young man with nothing more than cheap entertainment and American porn mags on the brain, with a pronounced need to avoid additional problems with teachers, police, neighbours, angry young women – and his father. Erhard had to teach him to see the bigger picture, to get past what his father said, to get past the girls’ glances. To build a layer of contemplation and preparation in between his spontaneous eruptions and his clumsy attempts at independence. Patience, in short. Some things had rubbed off on the boy, who had since become a man. And rubbed off so well that Raúl has become calmer, less confused, less frightening, happier. Even his father has noticed his development. Still, he doesn’t believe Erhard’s friendship was the cause of this transformation so much as the many years Raúl had spent being grounded, his ears boxed, his bank account regulated.

The result is a longstanding friendship, Erhard’s deepest and most alcoholic. Perhaps his only friendship. It’s a relationship in which Erhard is valued and has a voice, where he feels admired and accepted as the person he has been for the past two decades.

But it’s a wrongheaded, bizarre friendship according to TaxiVentura’s managing director Pauli Barouki. Because Raúl is on their competitor’s board of directors. Rumour has it that there’s a shady side to their friendship. They say that Erhard works for Raúl, that he gives him free rides or takes care of Raúl’s problems. But by and large they’re not even involved in each other’s lives. They talk about food, alcohol, arguments at the Yellow Rooster. Erhard tells stories about people from Corralejo or Raúl talks about the rich pigs, as he calls them, and their impossible love-lives, while Beatriz laughs. Neither of them want to know what the other does in his spare time. Raúl doesn’t want to hear about life as a taxi driver; every time Erhard complains about dispatch or the new rules for drivers, Raúl waves his hand the way he learned from his father. Nor does he want to hear about the books Erhard reads. And Erhard doesn’t ask Raúl about Taxinaria or where all of Raúl’s money comes from. He figures it’s his father’s, even though Raúl repeatedly says that he wants to earn his own money. Only that one time, with Federico Molino and the suitcase, did Erhard go too far for Raúl. It was illegal, but he did it for the right reasons. That’s what Erhard now thinks about the episode they haven’t spoken of since.

They gaze across the city and the beach. The water looks like marzipan.

Raúl shows him a wound on his knuckle. – Had a little disagreement with a seaman down at the Yellow Rooster, he chuckles. – He said things about my girlfriend.

Beatriz turns away, irritated. – I didn’t ask you to do that, she says.

– Was there no another way? Erhard asks, though he believes the three or four louts who fight in Corralejo usually deserve a beating. Erhard knows them; he’s driven them all home many times.

– You don’t know him, Raúl says. – But he deserved it. He’s been bothering me for months, years. But fuck that. No need to discuss it, right Bea? Salud.

He drinks.

They discuss the wine and the sunset and later the sunrise and the new boats anchored in the marina and Petra and her daughter, whom Raúl thinks is perfect for Erhard. To Raúl, it’s funny that Erhard has never really seen the girl, only her picture hanging on the wall of the salon.

– What is it with you and these women? Beatriz asks.

Raúl turns serious. – Erhard doesn’t talk about his past.

– There can be many reasons for that, Beatriz says.

– Watch it there, Bea, Raúl says.

– Are you afraid of love? she goes on.

Raúl lifts Erhard’s left hand so she can see the missing finger.

– Love has many faces, but only one asshole, Erhard says.

– Poetic, Raúl says. – Let’s just say: Being married is dangerous.

Beatriz shoves him. – You think it’s funny? Why do you talk about it like that?

– Tell Beatriz about the hairdresser’s daughter, Raúl says. – He’s almost met her five or six times, but he’s backed out every time.

It was more like four times. Including New Year’s Eve. But he doesn’t want to mention that.

– It was last year, I think. Or the year before that. The year when it rained the entire month of January.

– The year before, Beatriz says.

– I park the car, taking a break between jobs, and go down the street where Petra and her husband live. The daughter lived with them back then. The son goes to boarding school. I hear Petra through the balcony door. Have you heard Petra’s distinct Yorkshire accent?

Shaking her head, Beatriz laughs.

– And then her husband, he’s half-Moroccan, owns some electronic shops down in Puerto, among other things. They’re arguing about something involving their son’s school accommodation. I’m standing quietly in the doorway across the street, looking up, trying to catch a glimpse of the daughter Raúl keeps teasing me about. I probably stood there for an hour. Staring, following every little shadow moving across the ceiling, all the while figuring I’d see her on the balcony or in the big window next to it.

– You’re some kind of Hamlet, Raúl grins. Beatriz shushes him.

– You mean Romeo, Erhard says, and continues: – But I’m so preoccupied that I don’t even notice a person walking right past me, trailed by this sweet honeylike aroma. She crosses the street and enters the building. It’s not until the door of the flat closes and the argument abruptly stops and Petra says, Luisa, darling, her voice inflected by wine, that I realize the daughter had just walked past.

– What then? What then? Beatriz sits up.

– Nothing, Raúl says. – That’s what makes it so beautiful. It’s Erhard. Not a goddamn thing happens! Not a goddamn thing.

– What? Beatriz says. – You didn’t go up?

– I’m not meant to see her.

– What? Beatriz shouts excitedly. – Tell me you don’t believe that?

– I know a sign when I see one.

– But how do you know it’s a sign?

– I can see it. The pattern.

– Salud for Louisa, Raúl says.

– You can’t possibly believe that, Beatriz says, and drinks.

Erhard hopes, deep down, that Luisa is a slightly older version of Beatriz, with lips like Kirsten – a woman he shagged in the backroom of a bar in Horsens, Denmark, several decades ago – and an ass like one of the beach volleyball girls he’d recently driven down to Sport Fuerte. But the truth is she’s probably a rather average and sweet girl in a floral dress, with pale English breasts like her mother.

– Salud. Erhard sucks the rum and sugar from his glass and picks the mint leaves from his teeth.

– It’ll become an obsession, Beatriz says. – In ten years you won’t be able to think about anything else, and you’ll talk non-stop about her. Just you wait and see. Like those fishermen who finally, at long last, hook some monster fish only to lose it.

– She’s not that great, Raúl says.

Beatriz gives him an elbow.

– I’ve survived without a girlfriend, I think I’ll survive a little while longer.

– Seventeen years, Raúl says. – That’s because you live in a cave.

– It’s not as simple as you make it sound.

– I know that. But what if you only sent half of what you earned home, or a quarter? Then you’d have the money to do something else.

Erhard doesn’t want to discuss it.

– The ex-husband in Paradise, Raúl says to Bea. – He sends his entire fortune back to Denmark.

– That’s nice of you, Beatriz says.

– It costs money to save yourself. Isn’t that what you told me once? Wise words, Old Man. Raúl laughs. – My point is, living out there you don’t exactly have a dynamic social life. You need to go out and meet people.

– If I’m meant to meet someone, I will.

– Please stop with all that karma bullshit. If you’re so tired of the nickname Hermit, then come out of your turtle shell a bit more.

– His shield?

– Yeah, that too. Meet someone new, meet some ladies.

– Hey, I want to meet new people too. Why don’t we ever meet new people?

– We do. On the boat, et cetera.

– Yeah, old men with old money. I mean interesting people, like in Barcelona.

Raúl thinks it’s rubbish, that she’s just pissed. She has nothing to complain about, he says, his hand slipping under her dress. Erhard sits quietly, staring ahead. His eyes wander across the roofs which appear to be shimmying down and poking their antennae in the water. To turn it all in the right direction, he closes his eyes. When he opens them again, the terrace is empty. The chairs are empty, and everything’s tidied up. He’s lying underneath a thin blanket, and a small candle burns. The sky is heavy, blue, lifeless. The city light conceals the stars.

15

He picks up a woman. From the harbour in Corralejo, where she stood with her hair poufed out in every direction following the trip on the ferry, to Sport Fuerte, where she can’t find the address of the apartment in which she’ll live. She’s probably close to sixty. Her fingers are long and already brown and ringless. On top of that she’s Swedish, and she’s confused and nervous about something. They can almost communicate in their native languages, even though he’s forgotten much of the Swedish he once knew. She asks him about the necklace that’s dangling from the rearview mirror: a small, verdigrised pendant made of silver. It’s so dark out here, he says, and she laughs at him. In a wonderful way. She says it’s been an interesting ride. Slowly and methodically she drops the money into his hand, and he feels her fingers. That’s the kind of thing he misses.

But it won’t lead anywhere. He helps her retrieve her suitcase and she squats, puzzled, to rummage through her bag. She doesn’t give him her number – as he’d momentarily hoped she would – and she leaves his business card on the backseat along with a few papers from the ferry. He takes this as a sign. What else could it be? He’s too old and too ugly.

During siesta, he drives home and eats breakfast.

He lifts the finger out of his pocket. It’s light-brown and crooked; his own fingers are pink, except for his nails – they’re black. One’s nails turn black here on the island. The black dust that hangs in the air above settles onto everything and creeps underneath fingernails. He scrubs them with his shoe brush and washes them in the garden. Just not Bill Haji’s.

He uses duct tape to attach the finger to his left hand. The silver-coloured tape covers the joint, so it almost appears as though it’s a complete hand. He stands before the mirror admiring himself – hand dangling at his side, hand to his chin, arms crossed, thumb hooked in his trouser pocket. It’s a minor change, but it suits him. A new little finger. He almost feels normal, and can’t help but keep it on when he leaves.

A couple is standing near the roundabout outside of Puerto. He drives them to a bike-rental shop in Via Panitta. He changes gears and drums the wheel rhythmically. Neither one of them says a word to him. Neither one of them stares at his hand. They just talk about, well, something or other. Then he drives to La Oliva: A man and his dog are heading to the veterinarian. The dog, an old sheepdog, sits stock-still gasping for breath. Erhard’s afraid the dog will sniff the finger, but it seems more interested in the hollow space under the hand brake, where there’s a balled-up napkin from lunch. The man tells him the animal’s going to be put to sleep. There’s nothing that can be done, he says repeatedly. One hour later he drives them home. The dog continues to gasp for breath, but the owner is happy. We made it, he whispers to the dog.

16

Then comes the year’s first rainy day. Whenever it rains, he likes to be inside drinking Lumumbas. They don’t know jack about that down here, so if he’s at a hotel – he likes being at a calm, air-conditioned hotel with a bar, where the bartender stands quietly between fags – so if he’s at a hotel, he has to tell the bartender how to make a Lumumba. At the Hotel Phenix down on the beach in Corralejo, he once went behind the bar to show the new bartender how to heat up the cocoa with the same nozzle used to foam milk for a café au lait.

He’s at home today, where he keeps cocoa powder, powdered milk, and cognac on the top shelf of his pantry. The rainy season usually comes in the spring, as far as he’s concerned, but there are many different opinions on the matter here. He whips up cream with a fork attached to the power drill. And then he sits, shirtless, in his chair under the tarpaulin, gazing up at the mountain. Into the rain.

He put the finger in a glass of formaldehyde. The glass makes the finger appear elongated and thin. A pharaoh’s finger. A finger to make the heavens thunder. Up close, it’s just brown and twisted. The ring’s loose now; he can spin it, but it still won’t come off. It has begun to irritate him. If he can pull the ring off, the finger will seem more like his own. But he can’t let it dry out. Then it’ll break. Or fall apart. Like a crushed cinnamon stick.

The drops fall so thickly it sounds as if the earth itself is grumbling. As long as it keeps rai

ning, he can’t hear anything else. He thinks about the corrugated plastic sheet above the toilet and the kitchen, which makes everything sound much worse. For seventeen years he’s considered getting rid of it. It doesn’t match the house, and it sticks out like a sore thumb. But he doesn’t care about that, actually. It only irritates him when it bangs in the southerly wind and he lies in bed all morning cursing the wind or the roof or himself, because he didn’t replace that old plastic sheet years ago or, at the very least, lay some rocks on top of it so that it doesn’t bang as much. But when he’s outside sitting in front of his house and staring up at the mountain and the silver-coloured sky, he doesn’t think about anything.

When someone says, Isn’t it lovely to live in a place where it never rains?, he says, Yes. But the truth is, those four or five rainy days a year are what he loves most. They break up the monotony of sunshine; they’re like instant holidays pouring from the heavens. The entire island comes to a standstill. Everyone looks up or runs around finding the things they’ve left lying in the driveway, in the window, or on the terrace. And he doesn’t drive his taxi on those days. There are lots of customers when it rains, but he doesn’t want to waste a good rainy day. He parks the cab and sits under his tarpaulin drinking Lumumbas, until the thermos full of warm cocoa is empty. Then he falls asleep. If he’s at a hotel and gets drunk, he loans a room. More often than not, he knows the front-desk clerk. He throws himself fully dressed onto the bed. He doesn’t get hangovers from Lumumbas. It’s the good thing about Lumumbas.

17

A rapping. The roof’s banging in the wind. Or maybe it’s thunder.

It’s a knock at his door.

– Erhard. A voice penetrates the hard, steady rain. There is also thunder, but someone’s knocking on his door. Softly. He throws the blanket aside, stands up, and walks around the house. He doesn’t care about the rain. He likes to feel the cold droplets on his skin; they lead him farther and farther out of his ruminations or his sleep, into which he’d fallen. He recognizes the convertible and the figure waiting inside the car, behind the misted glass. Raúl’s pounding on the door. – I know you’re in there. Put down that Lumumba and come out.

The Hermit

The Hermit