- Home

- Thomas Rydahl

The Hermit Page 7

The Hermit Read online

Page 7

Why not?

He’d sat between those rocks himself once, horny as a bull, during his first seven months on the island. His skin becoming brown and hard. From morning to night he lay with an erection behind a rock, his rest interrupted only by short hikes down to the water. At night he slept under a ledge farther north up the coast. He’d light a fire and eat jellyfish or fish he caught himself. Mostly, he ate the leftovers from family picnics, heels of bread or hunks of sausage. If it got really bad, he walked to the supermarket and bought tins of food. He had money from home. Not much. A backgammon case stuffed with a few thousand euros. But he didn’t want to spend the money. For a long time he didn’t feel he deserved to spend the money. For a long time he just wanted to be left alone. Without smiling. Without any kind of pleasure. Not even the sunshine or the starlight. He lay quietly, dispassionately observing the sky. But in the end this proved difficult. In the end the small pleasures found him.

The sound of the water trickling through the rocks when the sea was at low tide. Warm bread from the fire. One morning, a large bird sat with a fish in its beak a metre away, dripping water and blinking its huge buttonlike eyes. Sometimes he had company. But only later, after a few months. People who wanted to see him for themselves el ermitaño, the man who lived among the rocks. Most of them just gawked at him, standing as far away as possible to watch him clamber about. Others came all the way up to his campfire and offered him food or asked him questions. But he never responded. In those seven months he said nothing. Not even when the two men attacked him with bats and beat him senseless, leaving him lying in the sun like a shelled turtle.

What doesn’t kill you makes you angrier, as the saying goes.

He parks his car and crosses the road to the flat section down the slope, steep and covered with chunks of rock. He notices that his left boot is in tatters. He notices his sock through a slit between the sole and the leather. It’s been a long time since he’s spent money on that sort of thing. He doesn’t like to. Just the thought of trying on shoes makes him delay buying them. Maybe he can mend it with a little glue or some duct tape.

The car was parked here, right here.

He walks up and down the slope. It looks like soft sand, but there are actually rocks right beneath the thin layer. It’s hard to walk on. Suddenly he’s standing in the water, the beach disappearing into it. Tidewater is distinctive across the entire island, but because the sandy bottom is so flat, it seems stronger here. Here, napping girls or some family on a picnic are suddenly surprised by a wave that crashes all the way up the beach and against the first row of rocks.

Erhard thinks about how the car must’ve gotten down the slope. Was it shoved? What did they want to happen to it? Did they want the car to sink into the sea? Was it supposed to have washed out into the waves and vanished? Why else would they push it down the slope? He’s seen some of the youths riding their ATVs down here. Was it a mistake that the car rolled down here? Had the mother somehow disappeared?

Maybe Raúl was right. He’d said that it was probably a car thief having some fun. But Raúl didn’t know there’d been a child in the backseat. That made it much worse.

Erhard gazes across the water.

If a person wanted to drown, all they would have to do was walk 100 metres out to the sandbank. The undertow is so strong out there that a body would wash ashore in Lanzarote in two days. He’s heard that from his colleagues who discuss Los Tres Papas, who earn their money from dry-cleaning businesses, coat-check services, gambling, and prostitution. Now and then they cut ties with a member or two, and that member washes up on the beach in Lanzarote, disintegrating and tender. Some rumours even have it that Raúl’s involved, but Erhard has never seen or heard anything that gives him any reason to believe it. Raúl may not always be a clean-cut kid, but he’s no criminal. People say a lot of stuff. Even about Erhard. They say he’s driven clients out to Vallebrón, and buried them underneath two metres of rock. At the beginning of the aughts, several bodies were found down there. Beneath rocks on which were carved three small matchstick men.

If the mother was the one who drove the car down the slope, then she must’ve been wracked with grief and shock. The boy lies dead or dying in a box in the backseat, she’s desperate, and maybe she’d drowned herself because there was nothing else she could do. That doesn’t explain the car. That it wasn’t registered. Or that it was wiped clean of fingerprints. A desperate mother wouldn’t clean fingerprints from her car. Besides, a tormented mother would leave behind an excuse, an explanation. To hurt a child is the most unforgivable act – that’s how it is in every culture the world over. Even in Catholicism, which otherwise revolves around forgiveness, it’s one of the sins one is least likely to forgive. But a mother from these islands would be unable to kill herself and her child without attracting attention. Too many things don’t add up. Erhard senses that the beach holds secrets. The car was abandoned here for a reason.

It’s like having twenty pieces to a puzzle and not knowing whether the entire puzzle has twenty-one or one thousand pieces.

In the supermarket he sees one of those kinds of boxes the boy was found in. Maybe not the exact same kind. But a simple, brown cardboard box with staples on the bottom along with a narrow slit. He removes the bags of rice and turns the box over.

He stares at the bottom and can almost see the boy, folded up, emaciated, alone. The tiny body clatters around. The little boy with the big eyes. And he sees a pair of hands that either put him in the box or aims to lift him out. Hands that either push him down into the darkness or hold him for the final time. Erhard doesn’t understand why it makes him angry, why it makes him so coal-black inside, why he can’t simply let it go. There are probably thousands of cardboard boxes across the globe with small children inside; one could no doubt fill an entire warehouse with them all. It’s the most brutal thing he’s ever seen, and he’s convinced someone took the boy there to die, but not the boy’s mother or father.

He puts the cardboard box down and buys tinned tuna.

On the way home he examines the finger taped to his hand, which rests on the wheel. It no longer resembles a finger, but a dry, spicy sausage. It looks terrible and it won’t fool anyone. Not even himself. Of course not. Of course it doesn’t work. He always recognizes the clients who’re wearing toupees. Only the most naive among them believe no one notices – everyone else knows it looks like a discoloured broom. But one can hope. One can pretend. He considers sending the finger to Bernal. Anonymously. With a friendly message. He considers burying it. He considers throwing it out the window while he’s driving.

Instead he finds a plastic container, one of those kinds used for food storage, with an airtight lid. He stuffs the finger inside a small, transparent baggie and then the container. He removes some books from his shelves and shoves the container in, then returns the books. He makes a note of which ones: Binario by Almuz Ameida and Victim on Third by Frank Cojote. He retreats a few steps; the bookshelf is now a wall of books, impossible to see that anything’s concealed there. Then he gets the tuna fish and eats directly from the tin, sitting on the edge of his chair, listening to the goats.

22

He has a new piano-tuning client on Monday morning.

Sometimes he gets new clients through his existing clients, but most hear about him from one of his fellow taxi drivers. If their conversations during the journey lead in that direction, they sometimes recommend the Hermit, even if they find it strange that he tunes pianos, too. Some time before Christmas, Alvaro – an olive farmer who went bankrupt last year and began driving a taxi – had told him that he’d given a lift to someone who wanted him to call her. The woman lived out in Parque Holandes and owned a Steinway that hadn’t been tuned in years.

– Why are you calling me only now? she said, when he rang on Christmas Eve, half in the bag and incapable of selling himself.

It was the beginning of a horrible conversation. Three times she asked him to speak

up and to think hard before he named his price. It’s a very expensive piano and there’s nothing wrong with it, she said, and negotiated more stubbornly than anyone he’d ever dealt with. They finally agreed on forty-six euros. Less than half his usual figure. Get here on the dot, was the last thing she said to him. Don’t waste my time.

He’s out there now, parked in front of the woman’s house, and looking at his clock. It’s past the agreed-upon time. But the radio’s tuned in to Radio Fuerteventura, and the news has just begun. The biggest news is that there’s been progress in discussions concerning salaries at the new casino. More than fifty employees are now…

As he’s listening, the door of the house opens. A woman stares at Erhard. A pretty woman. She’s wearing a white safari outfit, and she has white, maybe light-grey, hair. She waves as if to tell him that he may enter. He ignores her. The newscast has moved on to a segment on the EU, which is trying to help the Spanish economy by guaranteeing the nation’s banks, including Sun Bank, Fuerteventura’s largest. Many customers were nervous in January because…

The woman approaches the car. She looks like a widow. Relaxed, yet wearing high heels and some kind of glistening, flesh-coloured lipstick. When she gets close to him, he sees that her skin is stretched unnaturally tight across her cheekbones. She doesn’t seem friendly. At all. Erhard rolls the window down.

Just then, the newscast begins the segment that he’s feared.

A twenty-seven year old woman from Puerto del Rosario has confessed to abandoning a baby on the beach last week near Cotillo, where it…

– Señor Piano Tuner.

… of a car. When the car was discovered the baby was dead.

– Señor!

… now cooperating with the police to clarify the details in this unfortunate case. The police are positive that the mother herself is…

The woman’s head appears right next to the open window. – I’ve waited all day.

– Be quiet, Erhard says, turning up volume. – I need to hear this.

… not remanded into custody. A decision in the case and the woman’s punishment is expected before the end of…

The woman beside the car raises her voice so loud that he can’t follow the news. – I have never in all my life experienced such abysmal service. We had an agreement. I asked you to arrive on time.

The news segment is over. The story had sounded exactly as the vice police superintendent had laid it out to him. And as Erhard had feared. The world moves on to other news.

He glances to his left, where the woman glowers at him as if he’s about to leap out of the car. His entire nervous system wants to obey her stare, her command, but something holds him back.

– I’m not paying you one cent more than twenty euros. In fact, I should get a free tune-up if this is the way you treat your clients.

Erhard starts the engine.

– Stop, you can’t leave. I’ve waited all day. Her face looks as though it’s about to crack.

– There are more important things than your Steinway, Erhard says, before turning the vehicle around and heading towards the Palace.

Bernal is surprised to see him. – Hermit, he says.

– Is this what you meant by a local solution?

– Calm down. What are you talking about? Bernal guides Erhard behind an ordinary shelf with files and boxes stuffed with electric cables.

– This isn’t police work, damn it, this is nothing but…

– What? What is it?

– You and I both know that she’s not the one.

– And why not?

– Three or four days ago you had nothing, and you were frustrated. But now you’ve tied it all up in one neat little bow?

– It goes quickly once you have a lead.

– C’mon. You have no licence plate and a car with only thirty-one miles on the odometer? A girl from Puerto my ass.

– Watch your language, Hermit.

– Don’t you have any integrity?

Bernal whispers. – I told you we will not survive an unresolved case like this. It’s bad PR. We won’t let that happen. With the casino and all that.

– The casino? What does that have to do with anything?

– Get out of your cave, mate. The tourist industry is bleeding. If they build the casino on Lanzarote because we’re suddenly bad company, then a whole lot of people will lose their jobs.

– So what? You’ve charged some random mother so that we can have our casino?

– Of course not. We’ve concluded a nasty case that doesn’t have a happy ending.

– And what about the girl?

– She’s not a girl, she’s a woman, and she knows what she’s doing.

– Why did she do it then?

– Does it even matter, since she’s confessed?

Maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe it’s just Erhard. What the hell does he know about these kinds of things? It’s probably rare for all the pieces in a puzzle to fit together. – Where was the newspaper from? Erhard asks abruptly.

Bernal is irritated. – I’m sorry that I brought you into this. It’s a terrible case, also for me. But it’s over now. Just forget it. We’ve made an arrangement with her. It was her baby.

– An arrangement?

– Lower your voice. Yes, an arrangement. We’ve closed the case.

– Isn’t that just like Thomson and Thompson? An arrangement that gets exposed? Bernal, what have you done?

– My job. Goddamn it, you don’t know what it’s like. Bernal is losing his patience. – No one wants these kind of unsolved cases, regardless of how impossible they are to solve. The higher-ups tell us it needs to be closed.

– But why would she do it? Why would she let you do this to her?

– It’s a question of arguments, Bernal says, and Erhard knows at once that he means money. – If you’ve got nothing to lose.

– I don’t know whether I should feel bad for her or wish for her death, the dumb girl. Will she wind up in prison?

– First she’ll have a hearing before a judge, of course, but we’ll make sure she gets off easy, as far as the court’s concerned anyway. She’ll get what she needs. More than what she makes in her awful line of work now.

– A whore, in other words? You bought a whore? One of those dumb junkies? It’s only a matter of days before she…

– Weren’t you the one who called yourself Señor Againsttherules?

Erhard knows many of the island’s prostitutes. There are about twenty or thirty girls primarily working the tourists and a few wealthy men. He can easily picture one of them enthusiastically accepting the offer, her hand trembling. She won’t need to shag anyone, just pretend that she has, then given birth to a child she’s lost. Erhard searches for the finger in his pocket, then remembers that he no longer has it on him. He doesn’t get angry often, but he is now, and his ears are burning hot.

Bernal retreats a step. – Don’t look at me like that. I’m the only one who tried to solve this case. Trust me. I really thought you could help. One last stab at something. We didn’t know whether or not there was some kind of lead in all those newspaper fragments, but there wasn’t. They were dead ends.

– But it must mean something that the fragments were in Danish? You’ve got to follow the leads you find.

– But what does it actually mean? That the father was Danish? That the mother stayed at a hotel where they had Danish newspapers? That there are many Danish tourists here on the island? It doesn’t mean shit. They’re just newspaper fragments. In a few days the case will be completely over.

Silence. Bernal turns off the light.

– I’m going home, Erhard says.

– Thanks for all your help. Again.

If there was any sarcasm to Bernal’s words, it would add insult to injury, but it just seems like Bernal’s final attempt at being friendly.

They walk side by side through the office, out of the Palace, and down to the car park.

– I thought policeme

n became hysterical when little children were involved. That they stayed up all night turning over every stone.

– Trust me, I’ve stayed up late. Ever since we found him. We’ve turned over every fucking stone on this island. Sometimes there are shitty cases, and this is one of them. We’ve got our own lives to lead, too. You think it doesn’t haunt me to find a little boy like that? We can’t take it personally, for God’s sake, every time a child dies. At least now the case will be closed.

– When are you taking it to Armando?

– The hearing is at the end of the week. Friday morning.

They shake hands. Erhard likes Bernal, and that irritates him. – Goodbye Thomson, he says.

He drives out of the city. Heading north. He pushes the tape into the tape deck and John Coltrane begins his version of ‘Stella by Starlight’. In the side mirror he sees a plane emerging from a few wispy clouds. The sun’s rays make the wings appear as though they’re on fire.

23

He drives around without picking up anyone and without replying to dispatch. He listens to the radio, and every time he hears the segment – each time in a shorter or slightly revised version – he hears Bernal’s voice instead of the newscaster’s. No one wants an unsolved case.

He parks for half an hour out near the new casino. They’ve blasted the rocks away and levelled the cement, but they still haven’t built beyond one storey. The entire city is talking about the venture. The entire island. In the beginning it was just a project to create a few new jobs. But gradually, as ambitions grew, the casino was viewed as a way to save all of Corralejo, the island, and the Canary Islands, creating stability, growth, and happiness. According to Alphonso Suárez, head of the new casino, it’s a visionary construction, Corralejo’s new beating heart. Erhard is more sceptical. They’ve discussed the casino since 1999. They’ve already spent more than 30 million euros, but no one knows on what.

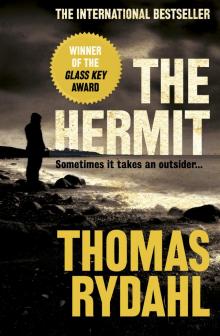

The Hermit

The Hermit